This is a chapter from a forthcoming book on education in the Maldives.

Before discussing the evolution of education policies in the years 1900–2015, it is instructive to trace the development of education in the Maldives prior to that period. The history of education in this period is a helpful background to understand the more recent eras.

Radiocarbon dating of the coral which constitute the islands has concluded that the islands were formed approximately 6000 years ago—recent in terms of geological time (Ali, 2000). The islands have been settled for at least 2250 years. Other evidence (the provenance of cowries found in face masks excavated from ancient Jericho) suggests an older ancestry going back to over 4000 years. From linguistic and epigraphical evidence, it is known that the early settlers were peoples from neighbouring Sri Lanka and the southern coast of India (Mohamed & Ragupathy, 2005). However, genetic ancestry testing shows that there is significant genetic diversity in the population since the Maldives is located on a major sea route.

The written history goes back only until 1153 CE when the Maldivians converted from Buddhism to Islam. The written script of the time, commonly known as eveylaa akuru, can be read by the learned Buddhist clergy of Sri Lanka. Other linguistic similarities also attest to the close association between Sri Lanka and the Maldives of the period. In Sri Lanka, the education of the Buddhist clergy is based on the Pirivena system.

Pirivena, derived from the Pali word ‘Parivena’ refers to the living quarters of the Buddhist monks. However, these pirivenas later became institutes of learning for the monks in Sri Lanka, especially for would-be monks. In fact, when the Chinese Buddhist monk, Faxian, visited the Kingdom of Anuradhapura in the 5th century CE, he was said to have seen over 3000 Buddhist monks in training. Today, the pirivena system of education in Sri Lanka is a complementary system to the prevailing public schooling and aims to educate both the bhikkhus or ordained male monks and males who wish to have their education in a Buddhist environment.

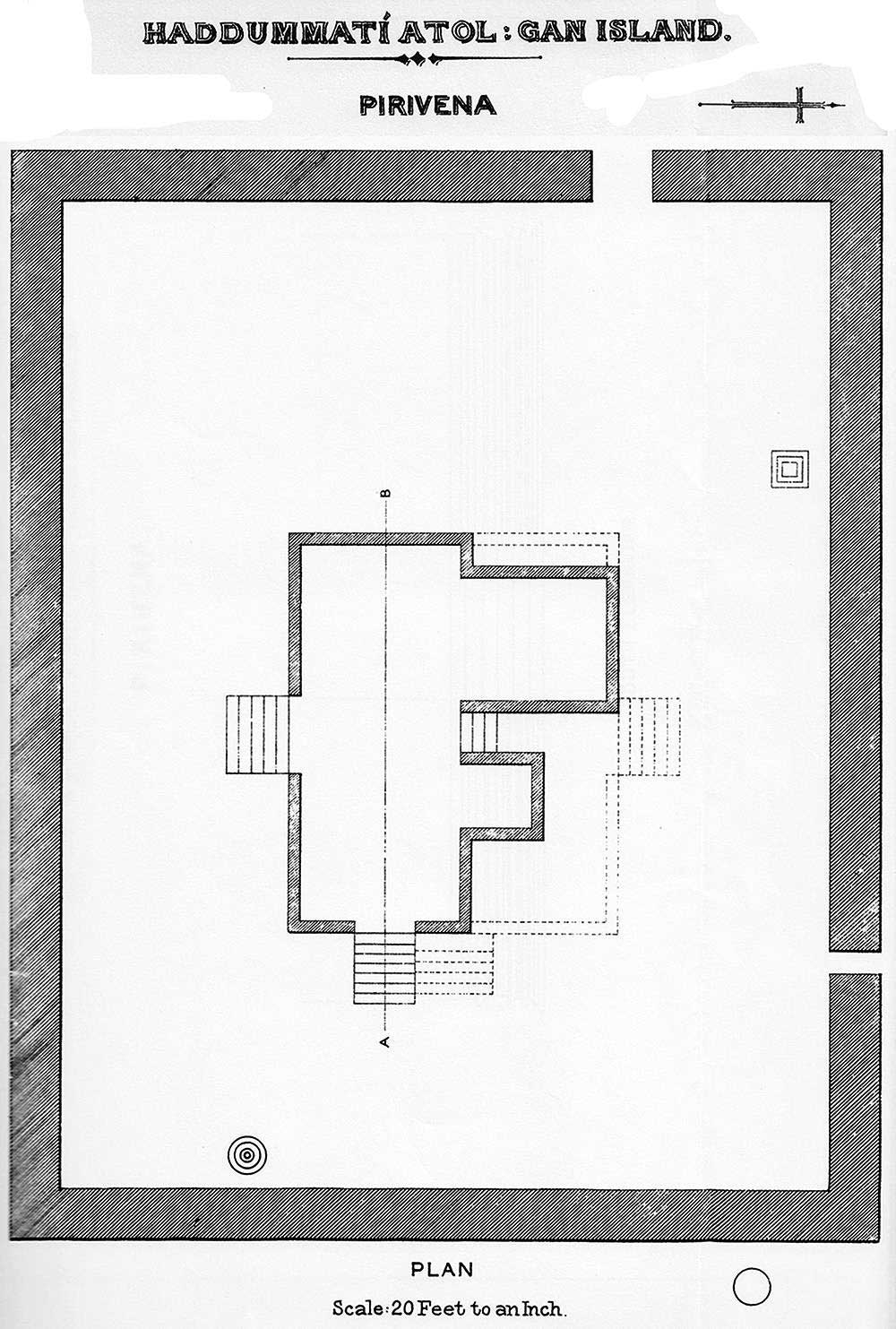

H.C. P. Bell, in his archaeological excavations in the Maldives, came across the ruins of at least one pirivena, and had included the layout of it in his monograph (Bell, 1940). It is reasonable to assume, given the cultural similarities between the Maldives and Sri Lanka, that some form of pirivena education was in existence in the years preceding the 12th century. If the Maldives was a Buddhist country, then local training of monks would be a necessity, and a few pirivenas of different levels would have been in existence in the country. In the 12th century, the population of the Maldives was likely to be no more than 10,000, and therefore, there would not be a necessity for many. Associated with pirivenas are bathing tanks. In Male’, the largest bathing tank was in Maafaanu district — Maaveyo, literally ‘huge bathing tank.’ When Bell visited the Maldives in the early 20th century, Maaveyo, measuring 25 feet by 75 feet was in existence. The tank was destroyed in the 1960s. Bell noted that there was no evidence of nearby pirivenas sometimes associated with bathing tanks. However, it is possible that the temple was replaced by a mosque when Maldivians embraced Islam. From the foregoing, we may surmise that the education for the general public was non-existent at the time. This was, indeed, the case for Sri Lanka and much of the Buddhist world. At pirivenas, the focus of training was on the practices of Buddhism and the ecclesiastical language, Pali. Chief monks would have been trained in the pirivenas of Sri Lanka.

An image of a pirivena from the monograph of H.C.P. Bell. Hadhdhummathi Atoll (Laamu Atoll) has ruins which can render useful information for historians.

In 1153 when, according to historical records, Maldives embraced Islam, there would have been a dramatic change in the lives of the people. History notes that the person responsible for the conversion was a Moroccan named Abul-Barakaathul Barubaree. The last name denotes that the person hailed from the Barbary States of North West Africa. Unlike Buddhism, Islam required reading and writing Quran for everyone, which would necessitate establishment of seminaries and schools. Education in religious practices cannot be conducted immediately upon conversion, and therefore, there would have been a gradual process of teaching the essentials of the new religion to the masses by training a few teachers.

Records of overseas visitors

Three overseas visitors to the Maldives between the years 1153 and 1900 had left written documents which mention sketchy details of prevailing methods of education at the time of their visits. One is Ibn Battuta the renowned Moroccan explorer who visited the Maldives in the 14th Century. The other was the Frenchman Pyrard de Laval who was shipwrecked in the Maldives in the 17th Century. The third were two surveyors who were sent by the British Admiralty to chart the Maldives in the earlier part of the 19th century and sojourned to write an account of the country.

The first of these, the Maghrebi Ibn Battuta, visited the Maldives in the reign of Queen Rehendhi Khadheeja in 1343 (744 AH). He visited the Maldives twice. From his records, one notes that he left the Maldives on 24th August 1344. For the second time, he arrived two years later. This time, however, he did not stay for long. He mentions that “orders of the Queen were written on palm leaves with a bent piece of iron similar to a knife, while paper was not used except for writing the Quran and books of learning” (The Rehla of Ibn Battuta, translated by Mahdi Husain, Baroda: Oriental Institute, 1976. p. 205). Ibn Battuta further mentions that some practices were against Islam and he endeavoured to rectify these practices to conform to fiqh.

From the above note by Ibn Battuta, one may gather that palm leaves and paper were used in the 14th Century in the Maldives. Ibn Battuta does not mention schooling as such, but his reference to ‘books of learning’ indicates the presence of knowledge other than those of Quran. There would have been a method for transmission of this learning as well. Informal schools such as edhuruge (literally teacher-house) must be present for the young to learn the practices of religion.

The most comprehensive account of the Maldives from the pre-1900 period is by Francois Pyrard. He was the navigator of a ship named ‘Corbin’ which shipwrecked on 3rd July 1602 near Goidhoo on its way to the East Indies. He stayed in the Maldives till February 1607. On his return to France, after several other adventures, he wrote a book on his voyages which was translated into English by Albert Gray with H.C.P Bell. Published by the Hakluyt Society of London in 1887, the translation is called The Voyage of Francois Pyrard of Laval to the East Indies, the Maldives, the Moluccas and Brazil. Pyrard writes:

About the age of nine months they begin to walk; and nine years they begin to be taught the studies and exercises of the country.

Their studies are to read and write, and to learn their Alcoran, and so to know how they have to live. Their letters are of three sorts; the Arabic, with some letters and points which they have added to express their language; another, whose characters are peculiar to the Maldive language; and a third, which is common to Ceylon and to the greater part of India. They write their lessons on little tablets of wood which are whitened and when they have learned their lesson they efface what have been written, and whiten them afresh, unless the writing is required to be preserved; in that case, they write upon parchment made of the leaves of the tree Macare queau [Maa kashikeyo], whose leave is a fathom and half long and a foot broad. They made books of it, which last as long or longer than ours, without decaying. In teaching their children to write, they use wooden boards make on purpose, well polished and joined, and spread thereon some fine, powdered sand; then they make the letters with a bodkin and bid them to imitate them, effacing betimes what they have written, a using no paper for this purpose. They all treat their masters with the same respect and honour as their own fathers, by reason whereof they may not contract marriage together, as though related in affinity,. Among them are men who make a pursuit of study, and are esteemed vastly learned in their knowledge of the Alcoran, and in the ceremonies of their law; these are chiefly the Moudins, Catibs or Naybes.”

Maakashikeyo was used earlier for making books. In other countries, the leaves are widely used to make mats, hats, bags, paper and baskets. Fibrous roots make coarse paint brushes. The flowers are used to cure scalp and skin ailments. The leaves and roots are used to treat leprosy, ulcers, skin diseases, flatulence, fever and diabetes. Utheemu Adambe (Adam Abdul Rahman), a renowned writer, remembers his father possessing books made from maakashikeyo leaves. Maakashikeyo is getting extinct in the Maldives. This type bears fewer fruit which are bigger than the common variety bearing smaller fruit.

The mode of schooling is not mentioned by Pyrard but it is noted that teaching children was a custom. The writing tablet mentioned called voshufilaa liyun continues to be used to date. The translators note that the Sinhalese use the same. At this time (early 17th century) edhuruge would have been the means of schooling. If organized State-sponsored schooling existed, undoubtedly, Pyrard would have mentioned it. Making books from written leaves of a special tree is a local adaptation of the centuries-old practice of writing on ola leaf in South Asia. No extant books of this type are to be found today in the Maldives although elders have noted that they had seen them. The Dhivehi word for document/deed is faiy which also means leaf.

Pyrard continues with other forms of education thus:

Mathematics are taught and much cultivated, especially astrology, which is studied by man, seeing that the astrologers are consulted at every turn. None would care to engage in any enterprise without previously taking their advice. …

These islanders practice themselves greatly in arms,—how to use the sword with the buckler, how to draw the bow with ease, how to fire the arquebuse and handle the pike; they also have schools of arms, whose masters are highly honoured and respected, they who take this office being in the general great lords. They have no other games but ball (large and small), which they catch and throw with much address, thought they use the feet only.

(Pyrard, 1887, 186–187)

That advanced forms of education and training were already prevalent at the beginning of the 16th Century are evidenced by the travelogue of Pyrard (1887). The emphasis on mathematics education, especially on astronomical and navigational calculations was corroborated by later writers, perhaps, because of its utility in voyages within and beyond the Maldives.

Training in arms was conducted in a specialised “school” in the 17th Century. Pyrard notes that there was only one such “school” sponsored by the government. A second one was started when a relative of the reigning king [Kalaafaanu] returned from overseas. The heads of these two were among the six people the king consulted on significant matters of the state. These six were known as havaru. The more recent account of education was written byYoung and Christopher in the third decade of the 19th Century.

In 1834, in the colonizing period of the British Empire, two surveyors, namely Young and Christopher, were landed in Male’ for a brief period to write a report on the Maldives because so little was known about it. About education, they note the following:

Children of both sexes are required to read the Koran through, under the tuition of priests of the inferior order, and their lesson is begun very early, — at three years of age. To be able to read, is all that appears to be thought necessary, and it is not pretended that more is attempted to be taught. When once through the Koran, the children receive no further instructions, except being initiated in the ceremonials of religion. The teachers are permitted by the parents to use a barbarous mode of punishing the children, if they show an aversion to learn Arabic, namely, that of squeezing lime-juice into their eyes, besides flogging and beating. As this cruel practice does not accord with the general character of the people, it is probably permitted only under a deep sense of the great importance of that branch of education in a religious point of view. As to the knowledge of writing, the children are left to acquire it themselves, fi they feel inclined, in the best way they can, and hence arises the great difficulty experienced in determining either the true sound of letters, or the orthography of words. Most of the boys, however, from a prevailing passion for music, soon gain a knowledge of the character, as all songs are written in it from the Persian or Hindoostanee, there being very few in their own language (p. 60).

A period of 230 years elapsed between the two records. Pyrard stayed for about four years in the Maldives whereas Young and Christopher stayed in Male’ for about 74 days. Actually, Christopher left Male’ for a while and returned later, both leaving on 17th August 1834. From both reports, it is known that children are taught Arabic literacy; Pyrard mentions that children were introduced to the language from the age of 7 years whereas Young and Christopher mention that teaching began from the age of 3 years. There is no mention of schools as such leaving us to deduce that edhuruge education was what was provided. There is no mention of government-sponsored schooling, nor makthabs or madhrasas. Pyrard mentions infantry training was provided in specialized training quarters which may be loosely termed as a military college. It is known that mathematics and astronomy were taught. Young and Christopher have not mentioned the existence of any kind of post-elementary training. However, mathematics and other branches of learning would be disseminated through teachers. An ongoing ancient practice is that of interested students attending private tutories to further their studies. Sometimes, students stay in the same compound or neigbourhood of the teacher while under his/her tutelage. Universities or colleges prevalent in the medieval Middle East and Europe were established in the Maldives.

Of the two accounts, that of Pyrard is likely to be more trustworthy owing to his longer stay, travel to other islands and richer details. The learning of Arabic noted by Young and Christopher relates to learning how to read and write Quran not to the language itself. The punishment meted out to young children they have stated appears to be a false perception arising from their short stay and an isolated personal experience rather than a traditional fact.

Renowned educators of the period

A renowned local scholar active in the middle decades of the 20th century, Mohamed Jameel, wrote a booklet on the early development of education in the Maldives. He noted that education in the Maldives was handed down from one scholar through a protégé to another. The government neither helped nor hindered this transmission of education viewing it as a private matter (Jameel, 1985, p. 9). Jameel lists the scholars through which education had been passed down the generations. It may be important to note that scholars in the middle ages considered education in a more holistic manner different from the comparmentalised discipline-specific specializations of the 20th century.

With regard to Barubaree, Jameel notes that he stayed in the Maldives educating the locals on the precepts and practices of Islam until his death. He is buried in Male’ in a mausoleum (Medhu Ziyaaraiy) most venerated by the educated locals (1985, p. 22). According to Jameel, after Barubaree, the next notable educator was another overseas scholar, Nooradhdheen Zaidhaanee, in the reign of Umaru Veeru (1306–1335 CE). As with Barubaree, these are Arabic-speaking travellers and traders whose ships frequently journeyed in the Indian Ocean during the Middle Ages. Ibn Battuta, the renowned explorer and scholar wrote that when he visited the Maldives in 1343, the Chief Justice was a Yemeni faqih named Easal Yamaanee. This scholar is another great teacher who spread education in the Maldives (Jameel, 1985). Following Easal Yamaanee, the next illustrious teacher was another faqih, Dhanna Muhammad who was again the Chief Justice in the period 1397 to 1409. It is a practice among many Islamic countries of the Middle East, Africa and India (which comprises a number of kingdoms at that time), that visiting scholars are made judges of the King’s court. In fact, Ibn Battuta himself was made a judge a few months after his arrival in the Maldives.

After Dhanna Muhammad, according to Jameel (1985), the next great educator was Faqih Hassan Shirazi, possibly from the Persian town of Shiraz. Local tradition states that this particular educator was put to death by the reigning king because he sentenced one of the King’s African slaves to death for a murder in 1497. Following Hassan Shirazi, the next great educator was Sulaiman from Medina of Arabia. Historical records note that these judges had students under their tutelage, and these students, in turn, taught others. However, for the general public, reading and writing of Quran would have been at a teacher’s house. Edhuruge is usually the teacher’s own house where he or she teaches students literacy and the essentials of being a Muslim. Edhuruge education survives till today providing a complementary education to the general public schooling. A teacher at an edhuruge could be either male or female. The teacher was paid in the past in kind by services rendered by the parents of the students or for free. All inhabited islands have edhuruges as of now. Edhuruge education is especially for young children learning to read and write Arabic and rudiments of Islam. For those who seek higher learning, the faqihs and their students were the tutors. Soon after the teaching legacy of Sulaiman of Medina waned, the Portuguese invaded Male’ (Jameel, 1985).

For almost all of its history, the Maldives has been an independent country reigned by kings and queens except for two brief periods of foreign invasions and short-lived imposed rule. In the first of these ‘interpositions’ the Portuguese, who were the dominant sea power in South Asia, were the aggressors. They invaded the country in 1558, killed the reigning king and took over the country propagating Christianity. The Portuguese were driven away 15 years later. Jameel notes that during the 15 years of Portuguese rule, it is not known whether the Maldivians learnt any education from the invaders. With the invasion, education descended into a brief period of darkness. While the reigning King was grieving the state of education, a Maldivian who had been studying various sciences in Hejaz for 30 years returned to the Maldives. When he was offered the post of the Chief Justice, he refrained imploring the King that he be permitted to stay in a small island by himself [“fushi rasheggai ekahesheen”] to spread education. And thus he retired to the island of Vaadhoo in Huvadhoo Atoll. He is generally known as Vaadhoo Dhanna Kaleygefaanu [Learned Sir/Master of Vaadhoo]. Soon after, students from across the Maldives came to Vaadhoo to study under him. However, most famous of his students were from the South of the Maldives: Huvadhoo Aboobakuru Fan’diyaaru Kaleygefaanu, Addoo Bodu Fan’diyaaru (Muhammad Shamsudhdheen) Thakurufaanu and Mulaku Dhoodigamu Edhuru Kaleygefaanu. Jameel notes that during those days, when the King wanted a Chief Justice he would send a missive to the South to obtain the service. Jameel states that the judicial and religious education present till 1900 was due to his teaching legacy, passing down the generations from one to another. Jameel (1985) lists 11 scholars, after Vaadhoo Dhannakaleygefaanu, who were famed for spreading education through their tutorage (Figure 1).

Eleven illustrious educators after Vaadhoo Dhanna Kaleygefaanu (Jameel, 1985)

1. Hassan Thaajudhdheen (Gan, Laamu Atoll. 1662–1727)

Education: Vaadhoo Dhanna Kaleygefaanu and Ghaazee Mahmood who studied from Ahmed Shihaabudhdheen of Addu Bodu Thakurufaanu. Also a student of King Sayyidh and faqihs of Mecca.

Services: Wrote Islamic books, Arabic poetry and Dhiveh history; Taught between prayers at Friday Mosque. The original of his history book was lost when marauders from South India burnt down the palace in 1725. A copy of the original manuscript gifted to Sri Lanka. A Dhivehi translation of his history book is extant. (Shihab, I. (1981). Dhivehi Thaareekh. Department of Information and Broadcasting, Male’.)

2. Muhammad Shamsudhdheen (born in present day Syria, d. 10th July 1692).

Education: Azhar University.

Services: Teaching and preaching. Teacher of Hassan Thaajudhdheen. Teacher of King Muhammad. Not known to have authored any books.

3. Ahmed bin Muhammad (Haajee Edhuru Kaleygefaanu. d. 1767).

Education: not included in Jameel (1985).

Services: One of his books extant (تحفةالولاة فى الأذكار والدعوات). His poetry is in local burudha books.

4. Abdul Hakeem bin Muhammad (Male’, d. 1713).

Education: Yemen.

Services: Taught many. His most renowned student is the author of “Bodu Tharutheebu”, Ali Edhuru Thakurufaanu.

5. Ali bin Muhammad (Ali Edhuru Thakurufaanu, Male’, d. 1730).

Education: Not listed by Jameel (1985). Abdul Hakeem Muhammad (above).Services: Travelled to the atolls to teach. His most famous work is the unprecedented fiqh book, “Ali Edhuru Bodu Tharutheebu” (زهرالكمالات فى أحكامالعبادات)

6. Muhammad Muhibbudhdheen (Sheikhul Islam, Gan, Laamu Atoll. d. 1785).

Education: Hassan Thaajudhdheen and Hussain Afeefudhdheen.

Services: Wrote the history of the Maldives from the ending date of the history written by Hassan Thaajudhdheen. The first scholar bestowed with the title of Sheikhul Islam. Other services not listed by Jameel (1985).

7. Ibrahim Siraajudhdheen (d. 1836).

Education: Muhammad Muhibbudhdheen (Sheikhul Islam).

Services: Wrote the history of the Maldives from the date of completion of history by Thaajudhdheen.

8. Ibrahim Majudhudhdheen (Meedhoo, Addu Atoll. d. 1870).

Education: His father Meedhoo Edhuru Thakurufaanu and Muhammad Muhibbudhdheen (son of Siraajudhdheen).

Services: Teacher to the famous scholars, Ismail Bahaaudhdheen Fadiyaaru Thakurufaanu, Dhonbeyya and Naibu Thuththu.

9. Ibrahim Bahaaudhdheen (Meedhoo, Addoo Atoll, 1864–1932).

Education: Arabia.

Services: Brought the first printing press to the Maldives, later gifted to the government. One of his books, Risaalath [Message], is extant. Another of his books is included in the first edition of Bodu Tharutheebu.

10. Ibrahim Thakurufaanu (Aisaabeege dharu Dhonbeyya, Meedhoo, Addoo Atoll. d. 1916)

Education: Majudhudhdheen.

Services: Teacher to Salaahudhdheen and others. Known for writing a book on local medicine. A short note on Dhonbeyya’s teaching style exists (Salaahudhdheen, H. (2008). Dhivehi adheebunge dhuvasvee liyuvvunthah. Novelty Printers and Publishers, Male’, p. 35).

11. Muhammad Jamaaludhdheen (Naibu Thuththu, d. 1905)

Education: Muhammad Muhibbudhdheen Fan’diyaaru Manikufaanu. Ibrahim Majdhudhdheen. Sheikh Musthafa (Beruwela, Sri Lanka), Zaidhi Dhahlaan (Mecca, Saudi Arabia), Umar (Yemen).

Services: Taught in several islands of the North, especially Naifaru. Several books on language, poetry and medicine. Tutor to Salaahudhdheen and Malim Moosa Maafaiy Kilegefaanu (official scribe in the latter part of the monarchy of the 20th Century).

Figure 1 summarizes the 11 scholars Jameel names after Vaddhoo Dhanna Kaleygefaanu. Jameel notes that the stream of education flowed through generations from teacher to student who in turn became a teacher and taught others. According to Jameel, there were two occasions when government intervened in providing education. The first was when King Ibrahim Iskandar who in 1659, upon return from pilgrimage to Mecca, caused a minor school to be established in the gateway to Friday Mosque of Male’ and employed a teacher to teach children the essentials of religious education. The gateway is a roofed structure with two benches on either side. What became of this minor school is not known. The school was certainly not functional long before the dawn of the 20th century.

Around 1882, the government again caused schools to be established in the four wards of Male’ called bandaara edhuruge (government teacher house) and appointed paid teachers. Instruction provided was in the basics of religious knowledge and literacy. Jameel notes that privately, students studied arithmetic and navigation from tutors without government support, and some excelled in these subjects.

Figure 1. Educators who made an impact on the Maldives from the 12th Century to the 20th Century were listed by Jameel (1985). There is little other information available to corroborate his findings.

Figure 1 summarizes the 11 scholars Jameel names after Vaddhoo Dhanna Kaleygefaanu. Jameel notes that the stream of education flowed through generations from teacher to student who in turn became a teacher and taught others. According to Jameel, there were two occasions when government intervened in providing education. The first was when King Ibrahim Iskandar who in 1659, upon return from pilgrimage to Mecca, caused a minor school to be established in the gateway to Friday Mosque of Male’ and employed a teacher to teach children the essentials of religious education. The gateway is a roofed structure with two benches on either side. What became of this minor school is not known. The school was certainly not functional long before the dawn of the 20th century.

Around 1882, the government again caused schools to be established in the four wards of Male’ called bandaara edhuruge (government teacher house) and appointed paid teachers. Instruction provided was in the basics of religious knowledge and literacy. Jameel notes that privately, students studied arithmetic and navigation from tutors without government support, and some excelled in these subjects.

Summary

Throughout the known history of the Maldives, educating the young in the essentials of religion had been practiced as a private enterprise. Advanced learning in mathematics and related sciences were conducted under the tutorages of those who have either studied overseas or locally. Only military training in Male’ was organized by the government.

The first public Government ‘school’ was established in the gateway to the Friday Mosque in about 1659. It is not known when this school ceased functioning. By 1882, there were four ward ‘schools’ providing essentials of religious knowledge and literacy. These schools, called ‘edhuruge’, are houses provided by the government for a teacher. Private edhuruge some of which may be loosely described as schools were common throughout history.

Jameel (1985) is the only text which lists names of some significant educators in religious sciences, language and literature before 1900. He lists the names of these educators, their services and their teachers. His assertion that the stream of knowledge passed down the generations from a teacher to students who later became teachers appears to be credible from what he had presented. No other sources to corroborate his findings have yet been discovered.

This is a draft excerpt from the forthcoming book by Aishath Ali, Hassan Hameed and Lesley Vidovich, “Education Policies of the Maldives: 1900 – 2015.” The reference list is in the book.

Other articles on Education are here.

Hi Dr Hassan, I found a reference in Hassan Taj Al-Din’s translation about a Al-Shaykh Muhammadh Jamal-al-Din from Hadramawt which i think is in Yemen. Is this the same person as Vaadhoo Dhanna Kaleygefaanu?

I hope it’s okay to provide a link here, please remove if links aren’t allowed

http://repository.tufs.ac.jp/bitstream/10108/84064/3/A505_3.pdf

Page 55

Thank you

Yes, I think so. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Hadhramaut

Hi Dr Hassan,

Thank you for writing the article, I wanted to reply within context of Vaadhoo Dhanna Kaleygefaanu’s origin.

The article implies that Vaadhoo Dhanna Kaleygefaanu was a Maldivian studying abroad for 30 years.

Taj Al-Din chronicles state that he was a migrant from Hadhramaut. Page 55 of the article under list of foreign muslim migrants to Maldives.

Appendix E: Page 55 http://repository.tufs.ac.jp/bitstream/10108/84064/3/A505_3.pdf

This is more logical towards him adopting the prefix “Vaadhoo” without having any association to another island.

Thanks

May I know citation to

“fushi rasheggai ekahesheen”

Uloomuge Gulshan 1 by Mohamed Jameel, 1985, See MNU Library OPAC

Thank you Dr Hassan. I enjoyed reading the article.I thought a system of education was not part of medieval Maldives. The Pirivina explanation has shifted my view of how I look at the place historically.

Found a typo. Anmes

He lists the anmes of these educators

Very interesting and informative. Thank you Dr Hassan and team for sharing this. Looking forward to reading the book.